Feb, 17 2026

Feb, 17 2026

When your body stops responding to insulin like it should, things start to fall apart-slowly, quietly, and often without warning. This is the core of type 2 diabetes, and it doesn’t start with high blood sugar. It starts with insulin resistance. And if left unchecked, insulin resistance doesn’t just lead to diabetes-it pulls in a whole cluster of warning signs known as metabolic syndrome. Together, they form a silent epidemic affecting nearly one in four adults worldwide.

What Is Insulin Resistance, Really?

Insulin is your body’s key to unlocking cells so glucose (sugar) can enter and be used for energy. When you eat, your pancreas releases insulin. It should tell muscle, fat, and liver cells: "Open up. Let the sugar in." But in insulin resistance, those cells stop listening. They become numb to insulin’s signal. So glucose stays in the blood. Your pancreas notices and tries to fix it-by pumping out even more insulin. That’s called hyperinsulinemia. For years, your body can keep up. But eventually, the beta cells in your pancreas get worn out. They can’t produce enough insulin anymore. That’s when blood sugar climbs into the diabetic range.

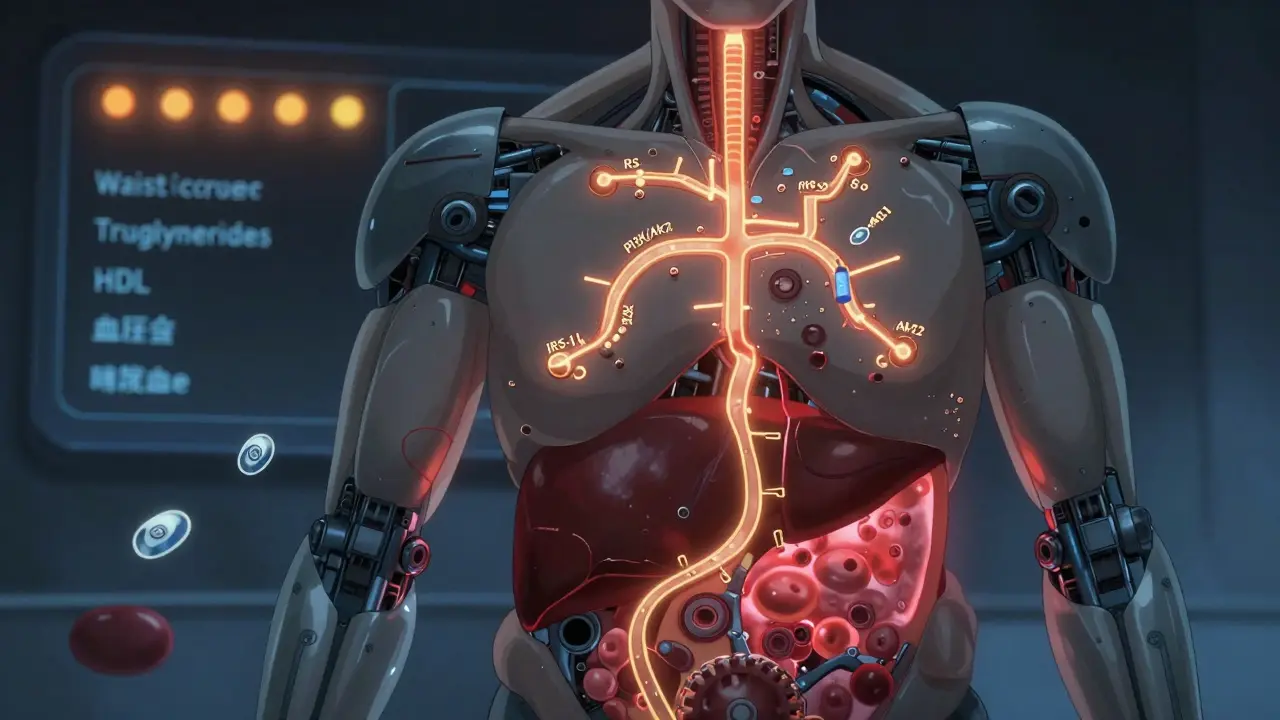

This isn’t just about eating too much sugar. The real trigger is chronic overnutrition-too many calories, especially from refined carbs and unhealthy fats. These flood your system with glucose and free fatty acids. They build up in places they shouldn’t: inside liver cells, inside muscle fibers, even inside fat cells. That messes up the insulin signaling pathway-specifically the IRS-1/PI3K/Akt2 chain. It’s like a broken lock. The key (insulin) still fits, but the mechanism inside won’t turn. Inflammation kicks in. Stress builds up in cell factories (endoplasmic reticulum). Oxidative damage piles up. And your body starts to store fat where it’s most dangerous: around your waist.

Metabolic Syndrome: More Than Just Being Overweight

Metabolic syndrome isn’t one condition. It’s five warning signs that show up together:

- Extra fat around your waist (≥94 cm for men in Europe, ≥90 cm for South Asian or East Asian men; ≥80 cm for women)

- Triglycerides at 150 mg/dL or higher

- HDL cholesterol below 40 mg/dL for men or 50 mg/dL for women

- Blood pressure at 130/85 mmHg or above

- Fasting blood sugar of 100 mg/dL or higher

You only need three of these five to be diagnosed. But here’s the thing: having just one doesn’t mean much. Having two? Still not too bad. But once you hit three? Your risk of heart attack, stroke, or type 2 diabetes jumps dramatically. The Mayo Clinic says your chance of heart disease more than doubles. And if you have fatty liver disease-especially nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-your risk of developing diabetes more than doubles too.

Not everyone who’s overweight has metabolic syndrome. Only 30-40% do. Why? Genetics. Some people store fat under the skin (subcutaneous), which is relatively harmless. Others store it inside the belly (visceral) and inside the liver. That’s the dangerous kind. That’s the kind that triggers inflammation and insulin resistance. That’s why two people can weigh the same, look the same, and have completely different health outcomes.

The Link Between Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Syndrome

Insulin resistance is the engine. Metabolic syndrome is the dashboard flashing red lights.

When your cells resist insulin, your liver keeps making glucose even when you don’t need it. Your fat cells release too many fatty acids into the bloodstream. Your muscles can’t take up glucose efficiently. Your blood pressure rises. Your good cholesterol (HDL) drops. Your triglycerides climb. Your waistline expands. All because insulin isn’t doing its job.

Doctors used to call this "Syndrome X." Now, experts are pushing to rename it metabolic dysfunction syndrome (MDS). Why? Because "syndrome" sounds like a collection of symptoms. But this isn’t just a list. It’s a cascade of biological failure. The term "dysfunction" better reflects what’s happening: your metabolism is broken at a fundamental level.

And here’s the hard truth: 80-90% of people with type 2 diabetes already had insulin resistance before they were ever diagnosed. That means the damage started years-sometimes decades-before the blood test came back abnormal.

How Prediabetes Fits In

Prediabetes is the middle ground. Fasting blood sugar between 100 and 125 mg/dL. HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4%. Your pancreas is still working hard, but it’s starting to strain. Beta cells are declining at about 4-5% per year in people who don’t change their habits. The Diabetes Prevention Program showed that people with metabolic syndrome have a 5 to 6 times higher chance of developing full-blown diabetes than those without it.

But here’s the good news: prediabetes is reversible. In the Look AHEAD trial, people who lost 10% of their body weight and exercised 150 minutes a week cut their diabetes risk by over half. And 51% of them saw their blood sugar return to normal within a year. That’s not a miracle. That’s physiology. When you reduce fat around your liver and muscles, insulin sensitivity improves. The cells start listening again.

What Works: Real-World Solutions

Medication helps-but it’s not the answer. Lifestyle changes are.

Weight loss: Losing just 5-7% of your body weight improves insulin sensitivity by 50-70%. For someone weighing 200 pounds, that’s 10-14 pounds. No need for extreme diets. Just consistent, moderate changes.

Exercise: 150 minutes a week of brisk walking, cycling, or swimming does more than burn calories. It makes your muscles more sensitive to insulin-even without weight loss. Strength training helps too. Muscle is the biggest glucose sink in your body.

Diet: Cut out sugary drinks. Reduce ultra-processed foods. Eat more fiber-vegetables, legumes, whole grains. Healthy fats from nuts, fish, and olive oil help reduce inflammation. Protein at every meal stabilizes blood sugar.

Medication: Metformin is the go-to for prediabetes with metabolic syndrome. It reduces diabetes risk by 31% over three years. Newer drugs like semaglutide (Wegovy, Ozempic) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro) don’t just lower blood sugar-they shrink fat, especially visceral fat. In trials, semaglutide led to nearly 15% weight loss over a year. Tirzepatide, a dual-action drug, pushed diabetes remission rates to 66% in some patients.

Monitoring matters. HbA1c should be checked every 3 months if you’re in the prediabetes or early diabetes range. Target? Below 5.7% for normal, below 7.0% for most with diabetes. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) like the Dexcom G7 are now FDA-approved for long-term use and give real-time feedback on how food, sleep, and stress affect your blood sugar.

Why This Matters Now

Right now, 537 million adults worldwide have type 2 diabetes. By 2050, the CDC predicts 1 in 3 Americans will have it. The economic cost? Over $327 billion in the U.S. alone. But it’s not just about money. It’s about quality of life. People with metabolic syndrome report constant fatigue, brain fog, intense hunger even after eating, and frustration when medications don’t seem to help.

And while drugs like GLP-1 agonists are revolutionary, they’re not forever. They work best when paired with lifestyle change. Lose weight, move more, eat real food-you can reverse the damage. Many people do. The body is built to heal, if you give it the right conditions.

The future is changing. Researchers are testing stem cell therapies to replace dead beta cells. New diagnostic criteria for metabolic dysfunction syndrome are coming by 2025. But the most powerful tool remains unchanged: awareness, action, and consistency.

What You Can Do Today

- If you’re overweight, especially with belly fat-start losing 5% of your weight.

- Walk 30 minutes a day, five days a week. Add two days of resistance training.

- Replace sugary snacks with nuts, fruit, or yogurt.

- Drink water. Skip soda, juice, energy drinks.

- Get your HbA1c and fasting glucose tested if you haven’t in the last year.

- If you have three or more signs of metabolic syndrome, talk to your doctor about metformin or a referral to a lifestyle program.

You don’t need a perfect plan. You just need to start. And keep going.

Can you reverse insulin resistance?

Yes, especially in the early stages. Losing 5-7% of body weight, exercising regularly, and cutting processed carbs can restore insulin sensitivity within weeks to months. The liver and muscles start responding to insulin again. Studies show that people with prediabetes who make these changes can prevent type 2 diabetes entirely.

Is metabolic syndrome the same as type 2 diabetes?

No. Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of risk factors that increase your chance of developing type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Type 2 diabetes is a specific diagnosis based on persistently high blood sugar. Most people with metabolic syndrome are on their way to type 2 diabetes-but not everyone gets there. Lifestyle changes can stop the progression.

Why do some thin people get type 2 diabetes?

About 10-20% of people with type 2 diabetes are not overweight. This is often linked to genetics, especially in South Asian populations. Even at a normal weight, if fat is stored inside the liver or muscles (ectopic fat), insulin resistance can develop. It’s not about total body fat-it’s about where the fat is stored.

Does metformin help with metabolic syndrome?

Yes. Metformin improves insulin sensitivity, lowers liver glucose production, and reduces fasting blood sugar. It’s recommended for prediabetes with metabolic syndrome because it cuts diabetes risk by 31% over three years. It may also help lower triglycerides and blood pressure slightly, though lifestyle changes are still the most effective.

How long does it take to improve insulin sensitivity?

You can see measurable improvements in as little as 2-4 weeks with consistent exercise and dietary changes. Weight loss and reduced liver fat take longer-typically 3-6 months for significant gains. But the key is consistency. Even small daily habits add up. One study showed that people who walked 10,000 steps a day improved insulin sensitivity by 20% in just 8 weeks.

Can you have metabolic syndrome without being obese?

Yes. While obesity is the most common cause, you can have metabolic syndrome with a normal BMI if you have high visceral fat, elevated triglycerides, low HDL, high blood pressure, or high fasting glucose. Genetics, sedentary lifestyle, and poor diet can cause this. Waist circumference is a better indicator than weight alone.