Nov, 17 2025

Nov, 17 2025

One in every 20 children has a vision problem that could lead to permanent vision loss-if it’s not caught early. That’s not a rare outlier. It’s the norm. And yet, many parents and even some pediatricians don’t realize how simple, quick, and life-changing a five-minute vision screening can be. By age 7, the window for fixing conditions like lazy eye or crossed eyes begins to close. After that, treatment becomes harder, less effective, and sometimes impossible. The good news? We know exactly how to find these problems before they stick. We just need to do it consistently.

Why Screening Before Age 5 Matters More Than You Think

The human eye doesn’t fully develop on its own. It needs clear, balanced input from both eyes during the first few years of life. If one eye is blurry, crossed, or blocked, the brain starts ignoring it. That’s amblyopia-lazy eye. It’s not a muscle problem. It’s a brain problem. And once the brain learns to ignore the weaker eye, it rarely goes back. Studies show that when amblyopia is caught before age 5, 80 to 95% of children can regain normal vision with treatment. But if it’s found after age 8, success drops to just 10 to 50%. That’s not a small difference. That’s the difference between seeing clearly for life or living with permanent vision loss in one eye.

Strabismus-where the eyes don’t line up-is another silent threat. It doesn’t always look obvious. A child might turn their head slightly, squint in bright light, or close one eye when reading. These aren’t just quirks. They’re warnings. Left untreated, strabismus can lead to amblyopia, depth perception issues, and even social stigma as kids grow older. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Ophthalmology, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force all agree: screening between ages 3 and 5 is non-negotiable. It’s a Grade B recommendation-the same level given to childhood immunizations and blood pressure checks.

What’s Actually Tested During a Pediatric Vision Screening

Screening isn’t one-size-fits-all. It changes as kids grow. For babies under 6 months, doctors check the red reflex-the glow you see in photos when light hits the retina. A dull or uneven glow can mean cataracts, retinoblastoma, or other serious conditions. This test takes seconds. No cooperation needed.

From 6 months to 3 years, providers look at eye movement, pupil response, and eyelid health. They check if the eyes track together, if one drifts inward or outward, and if the pupils react normally to light. These are basic but powerful clues.

Starting at age 3, visual acuity testing begins. This is where charts come in. But not the big Snellen charts you remember from the doctor’s office. For little kids, it’s symbols: circles, squares, apples, or letters like H, O, T, V. These are easier to recognize than letters. The standard is the LEA Symbols or HOTV chart. At age 3, a child needs to read the 20/50 line. At age 4, it’s 20/40. By age 5, they should hit 20/32. If they miss more than one or two symbols on the critical line, they’re referred for a full eye exam.

Distance matters. The chart must be exactly 10 feet away. Too close, and a child might guess correctly. Too far, and they can’t see it at all. Lighting? It has to be bright and even. Shadows or glare can ruin the test. And each eye is tested separately. Covering one eye at a time is key. Many kids will use their stronger eye to compensate if both are open.

Old School Charts vs. New Tech: What Works Best

There are two main ways to screen: traditional charts and instrument-based devices. Both have strengths.

Optotype-based screening (charts and symbols) is the gold standard for kids who can cooperate. It’s low-cost, widely available, and doesn’t need batteries. But it fails when kids are shy, tired, or don’t understand the task. Up to 25% of 3-year-olds can’t complete it reliably. That’s why many clinics now use instrument-based tools.

Devices like the SureSight, Power Refractor, and blinq™ scanner measure how light reflects off the retina to detect refractive errors-nearsightedness, farsightedness, astigmatism-before a child even says a word. The blinq™ scanner, FDA-cleared in 2018, uses AI to analyze images and flags cases of amblyopia or strabismus with 100% sensitivity and 91% specificity. It takes 1 to 2 minutes per child. No chart. No answers. Just point, click, and go.

Here’s the catch: instrument-based screens can overcall. A child might have a tiny refractive error that’s normal for their age, but the device flags it anyway. That leads to unnecessary referrals. That’s why experts recommend using these tools for kids who can’t do chart tests-not as a total replacement. For a 5-year-old who can read HOTV letters? Stick with the chart. For a 2-year-old who won’t sit still? Use the scanner.

Who Should Be Screening, and How Often?

It’s not just the eye doctor’s job. Pediatricians, family doctors, nurses, and even school staff can-and should-do screening. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vision checks at 8, 10, 12, and 15 years, but the real window is 3 to 5. That’s when most problems are fixable. That’s why Bright Futures guidelines, adopted by 47 U.S. state Medicaid programs, require vision screening at every well-child visit between ages 3 and 5.

Training is straightforward. A 2- to 4-hour session is enough for most providers to become proficient. The National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health offers free online modules used by over 15,000 professionals. Quality checks every quarter help avoid mistakes-like holding the chart too close or misreading the referral line.

Screening isn’t optional in most states. Thirty-eight states require vision screening before school entry. But standards vary. Some use outdated charts. Others skip the red reflex test for infants. The goal is consistency: every child, every time, with the right tool for their age.

What Happens After a Positive Screen?

A positive screen doesn’t mean your child has a disease. It means they need a full eye exam by a pediatric ophthalmologist or optometrist. That’s the next step. No delays. No "wait and see."

Most insurance plans cover this under the Affordable Care Act’s pediatric essential health benefits. If you’re on Medicaid, it’s required. If you’re uninsured, community clinics and programs like Vision to Learn offer free screenings and exams.

Treatment depends on the issue. For amblyopia, it’s usually patching the stronger eye for a few hours a day to force the weaker one to work. Glasses fix most refractive errors. Strabismus might need glasses, vision therapy, or surgery. The earlier treatment starts, the less invasive it is. A 4-year-old might need glasses and a patch for 3 months. A 10-year-old might need surgery and months of therapy.

Don’t wait for symptoms. Many kids with vision problems don’t complain. They assume everyone sees the world the way they do. That’s why screening isn’t about waiting for a child to say, "I can’t see the board." It’s about finding the problem before they even know it exists.

Barriers and How to Overcome Them

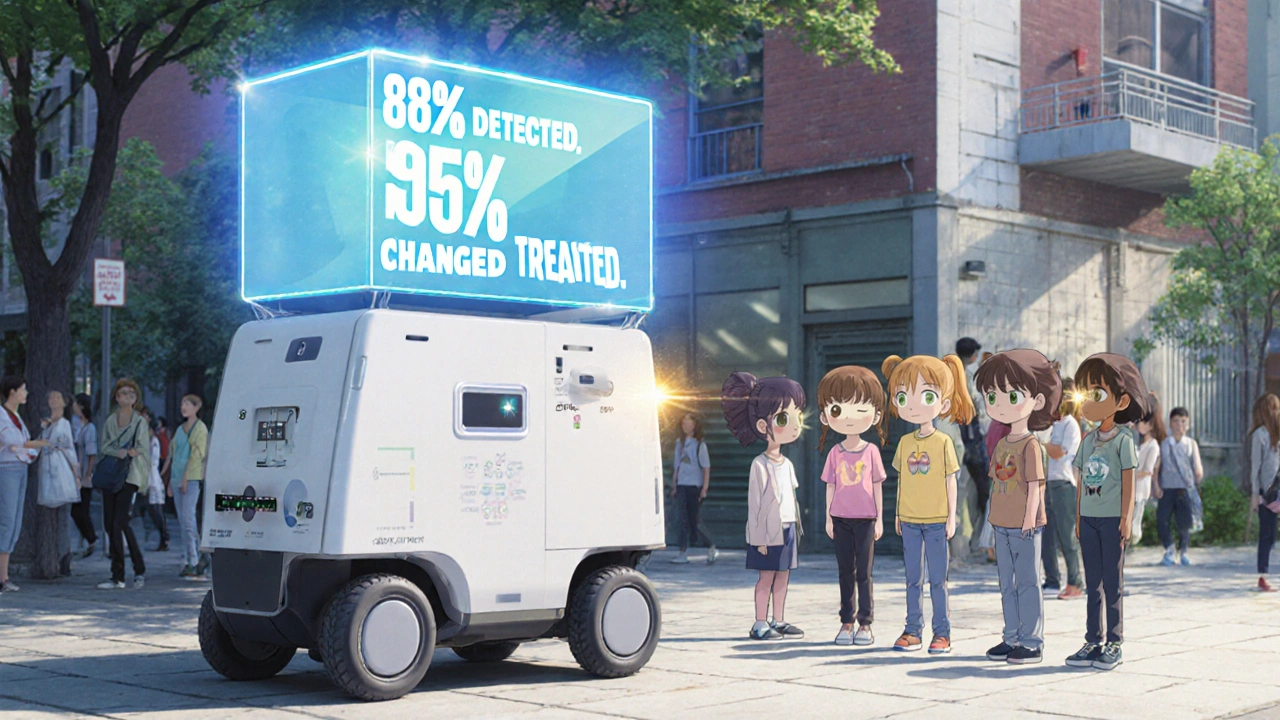

Despite the evidence, screening gaps remain. Hispanic and Black children are 20 to 30% less likely to get screened than white children, according to the National Survey of Children’s Health. Why? Access, awareness, language barriers, mistrust in the system. Mobile screening units, multilingual materials, and community outreach programs are helping-but not fast enough.

Another problem? Cost. A SureSight autorefractor runs $5,500 to $7,000. A blinq™ scanner is $3,500. For small clinics, that’s a big investment. But the return? The USPSTF calculated a 3.7:1 benefit-to-cost ratio. Every dollar spent on screening saves $3.70 in lifetime costs from untreated vision loss-lost productivity, special education needs, reduced quality of life.

Don’t let cost stop you. Many states offer grants. Nonprofits donate equipment. The real cost isn’t the machine. It’s the child who grows up with one good eye.

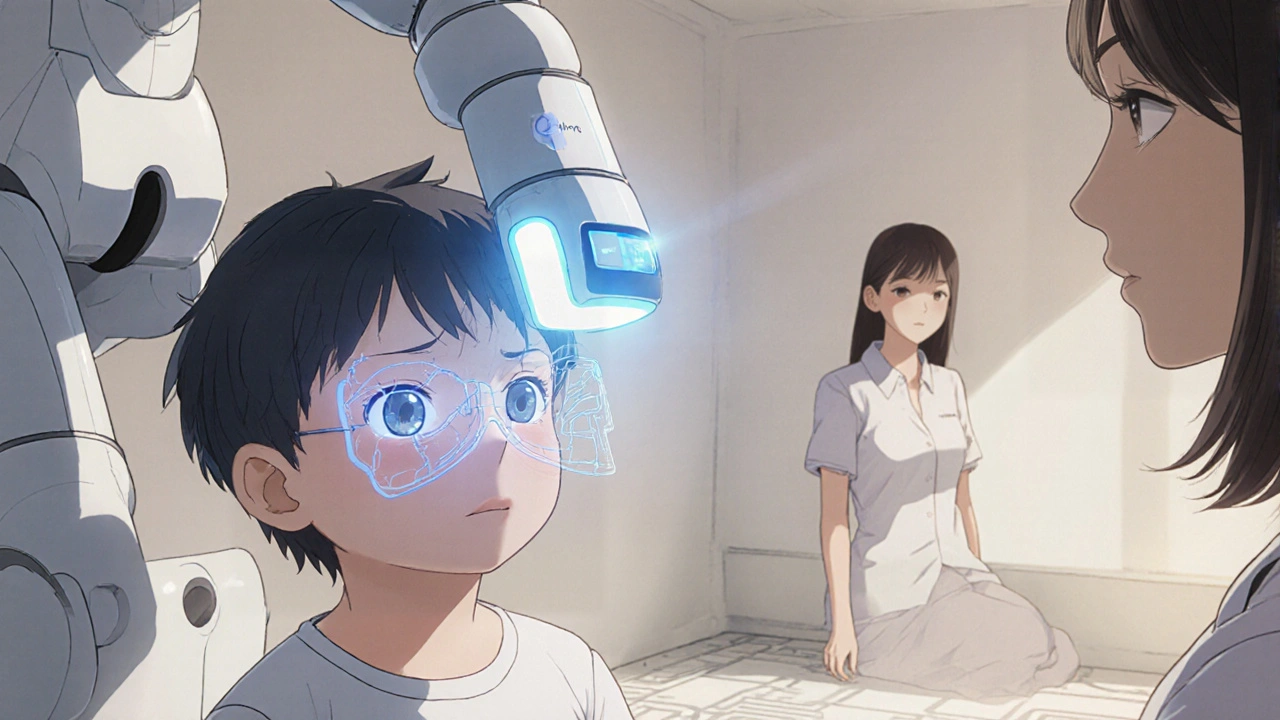

The Future: AI, New Tools, and Broader Screening

The blinq™ scanner was the first AI-powered device cleared by the FDA for pediatric vision screening. It’s not the last. The National Eye Institute is funding $2.5 million in research to improve accuracy in diverse populations. Early studies show instrument-based screening works as young as 9 months. That could change guidelines soon. The AAP is expected to update its recommendations by 2025, possibly recommending screening starting at age 1.

What’s clear? The future of pediatric vision screening isn’t about replacing doctors. It’s about giving them better tools to catch problems earlier, faster, and more fairly. The goal isn’t just to see better. It’s to make sure every child has the chance to see at all.

What is the most common vision problem in young children?

The most common vision problem is amblyopia, or lazy eye. It affects 1.2% to 3.6% of children. It happens when one eye doesn’t develop normal vision because the brain ignores it-often due to a refractive error or misaligned eye. Strabismus, where eyes don’t line up, is the second most common, affecting about 1.9% to 3.4% of kids. Both are treatable if caught early.

Can a child pass a school vision screening and still have a problem?

Yes. School screenings are often basic and only test distance vision. They may miss farsightedness, astigmatism, or subtle eye alignment issues. A child might pass the 20/40 line but still struggle with reading or depth perception. A full eye exam by an eye care professional is the only way to be sure.

Is vision screening covered by insurance?

Yes. Under the Affordable Care Act, pediatric vision screening and diagnostic eye exams are considered essential health benefits. Most private plans, Medicaid, and CHIP cover them at no cost to families. Some states also require insurers to cover the cost of glasses if needed after a screening.

How often should my child be screened?

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening at ages 3, 4, and 5, and then again at 8, 10, 12, and 15. The most critical window is between 3 and 5 years old. If your child has risk factors-premature birth, family history of eye problems, developmental delays-screening should start earlier and happen more often.

What if my child refuses to cooperate during screening?

It’s common, especially with 3-year-olds. Don’t force it. Try again in a few weeks. Many clinics use instrument-based screens like the blinq™ or SureSight for uncooperative kids. These devices work without verbal responses. If screening fails twice, refer for a full exam. Waiting too long risks permanent vision loss.

Are there signs I can watch for at home?

Yes. Watch for squinting, tilting the head, closing one eye to see, sitting too close to the TV, frequent eye rubbing, or avoiding activities like puzzles or coloring. If your child complains of headaches after reading or has trouble catching a ball, it could be a vision issue. These signs aren’t always obvious-especially in toddlers-but they’re worth investigating.

Early detection doesn’t require fancy equipment or long visits. It requires attention. It requires knowing what to look for. And most of all, it requires acting before it’s too late. One screening. One moment. One chance to change a child’s future.

kora ortiz

November 17, 2025 AT 20:17Every child deserves to see the world clearly-no excuses. If your kid’s not screened by 5, you’re gambling with their future. It’s not complicated. Do the test. Save the vision. Period.

Kathryn Ware

November 18, 2025 AT 07:38OMG YES 😭 I’m a pediatric nurse and I’ve seen too many kids come in at age 8 with lazy eye and their parents say ‘but they never complained!’ Like… they don’t know any different. One little 4-year-old girl finally got glasses after her screening and cried because ‘the trees have leaves now’-like she’d never seen individual leaves before. It’s not just about reading the board. It’s about seeing fireflies. Seeing your mom’s smile without squinting. Seeing life in focus. 🌈👁️🗨️ And honestly? The blinq™ scanner changed everything in our clinic. We went from 30% non-compliance to 95% success rate with toddlers. No more tears, no more ‘I can’t read that’-just a quick flash and boom, we know. Please, if you’re reading this, don’t wait for the school screening. Do it at 3. Don’t wait for symptoms. The brain doesn’t wait.

Jeremy Hernandez

November 18, 2025 AT 20:34So let me get this straight-now we’re scanning babies’ eyes with AI because the government says so? Next they’ll be implanting trackers in newborns’ eyeballs. Who’s really profiting off this? The device companies. The ‘experts’ who get grants. The schools that don’t wanna deal with kids wearing glasses. And meanwhile, my cousin’s kid got diagnosed at 6 because he kept bumping into stuff-no screening needed. Just good ol’ parental observation. This whole system is overmedicated and overtested. Stop pushing tech on toddlers. Just watch your kid.

Holli Yancey

November 19, 2025 AT 12:10I get the urgency, but I also wonder… how many kids are getting unnecessary referrals because of overzealous screening? I had a friend whose 3-year-old was flagged for astigmatism-turned out it was just a tiny, harmless irregularity that resolved on its own. The anxiety, the extra appointments, the cost… it adds up. Maybe we need more nuance-not just ‘screen everyone, everywhere, always.’

Tarryne Rolle

November 21, 2025 AT 07:35Is vision screening really about children… or about controlling how we perceive reality? The brain ignores the weak eye not because it’s broken, but because it’s adapting. We pathologize adaptation. We force symmetry. We medicate perception. What if the ‘lazy eye’ isn’t a defect-but a different way of seeing? A quiet rebellion against the tyranny of binocular vision? We’ve made seeing a moral obligation. What if we just… let them see differently?

saurabh lamba

November 22, 2025 AT 09:34USA spending $7000 on a machine for 2-year-olds? In India we just use flashlight and watch for red reflex. No AI. No cost. No fuss. Why overcomplicate? Your system is broken. You make money from fear. We fix with common sense.

Kiran Mandavkar

November 23, 2025 AT 18:08Pathetic. You’re all falling for corporate propaganda. The ‘FDA-cleared’ blinq™ scanner? Designed by the same people who sold you 5G autism and gluten-free water. You think a $3500 gadget can replace parental intuition? Or the centuries-old art of watching a child interact with light and shadow? This isn’t medicine. It’s tech-washing. And you’re the sheep buying it.

Shannon Hale

November 25, 2025 AT 10:57I’M SO FURIOUS RIGHT NOW 😤 I had a friend whose daughter was diagnosed with amblyopia at 7 because her pediatrician said ‘she’ll outgrow it.’ SEVEN YEARS OLD. She’s now 14 and still struggles with depth perception. She can’t play soccer. Can’t drive. She wears an eye patch like a badge of shame. And it was all preventable. This isn’t just ‘screening’-it’s a civil rights issue. Every child, regardless of zip code, deserves a shot at full vision. If your clinic doesn’t have a SureSight or a blinq™, you’re failing them. And if you’re a parent and you skipped the screening because ‘it’s not necessary’-you’re part of the problem.

Gordon Mcdonough

November 26, 2025 AT 15:38WHO IS PAYING FOR THIS?!?!? I’m a single dad. I work 2 jobs. I don’t have time for ‘screenings’ and ‘referrals’ and ‘eye doctors’-my kid’s fine! He sees the TV! He catches the ball! Why do they keep pushing this? Is it the insurance companies? The eye doctors? The government? Someone’s making bank off scared parents! And now they want to scan babies at 9 months?!?!? What’s next? Mandatory DNA eye tests? I’m not doing it. My kid’s not a lab rat.

shubham seth

November 27, 2025 AT 11:02Let’s be real-90% of these ‘vision problems’ are just lazy parenting. Kids don’t need a machine to tell them to stop sitting too close to the screen. They need discipline. A good slap. A rule. No screens before 6pm. No iPad during meals. No whining about ‘I can’t see.’ You want to fix vision? Fix the environment. Not buy a $5000 gadget to avoid responsibility. This whole thing is a distraction from the real issue: we’ve turned kids into fragile, screen-addicted zombies. And now we’re blaming their eyes.

Kyle Swatt

November 28, 2025 AT 23:12I used to think this was overkill. Then my son was screened at 3 and found to have a subtle refractive error. We got glasses. He started reading books on his own. He drew his first full-color picture without squinting. He smiled more. I realized-this isn’t about medicine. It’s about giving a child their first real taste of wonder. The way light hits a puddle. The texture of a leaf. The face of a friend across the room. That’s what we’re protecting. Not just vision. Experience. Curiosity. Joy. And yeah, it’s worth every minute, every dollar, every awkward moment of holding up a chart to a toddler who’d rather eat it.

Deb McLachlin

November 29, 2025 AT 14:39While the intent behind universal screening is commendable, the implementation remains inconsistent across socioeconomic strata. The disparity in access to instrument-based devices between urban and rural clinics, as well as among Medicaid-enrolled populations, raises significant equity concerns. Without standardized training protocols and equitable funding mechanisms, technological innovation risks exacerbating existing disparities rather than mitigating them. A systemic approach, not merely a technological one, is required.

Eric Healy

November 29, 2025 AT 23:36Look I’m not saying this isn’t important but my kid got screened at school and they said she was fine. Then we went to the eye doctor and she needed glasses. So school screenings are useless. Why are we even doing them? Waste of time. And the chart thing? My 4-year-old didn’t know what a circle was. She thought it was a cookie. So now what? We need better tools. Or just tell parents to take their kids to the doctor. Done.

Jessica Healey

December 1, 2025 AT 08:39I’m so tired of people acting like this is just about kids. It’s about control. They want to monitor everything. From your kid’s eyes to your grocery cart. They’re normalizing surveillance under the guise of ‘health.’ I’m not letting my 2-year-old get scanned by some AI device that doesn’t even know what ‘no’ means. My child’s body is not a data point. I’m not participating.