Jan, 21 2026

Jan, 21 2026

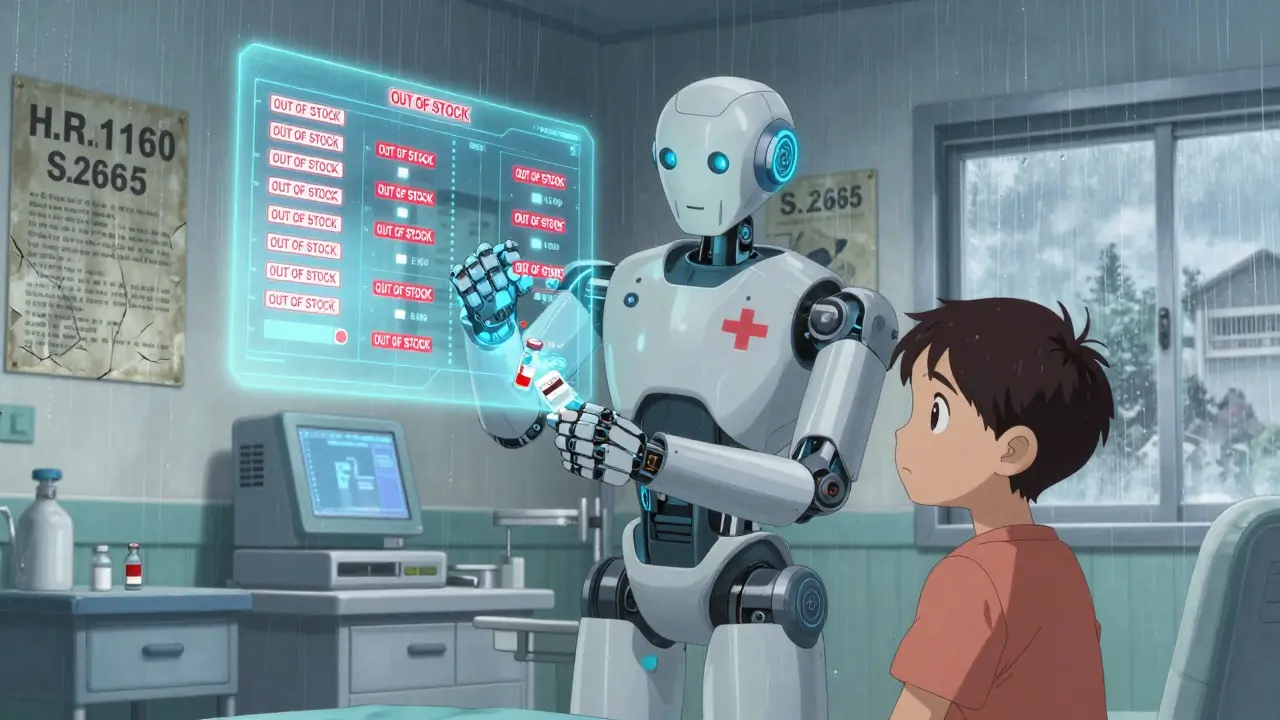

Right now, over 287 drugs are in short supply across the U.S., and nearly half of them are critical medicines for heart attacks, cancer, and severe infections. Hospitals are rationing doses. Doctors are calling patients to say their treatment is delayed. And Congress is sitting on two bills meant to fix this - but they’re stuck, frozen in place by the longest government shutdown in American history.

What’s Actually in the Two Key Bills?

The most concrete effort so far is Drug Shortage Prevention Act of 2025 (S.2665). Introduced by Senator Amy Klobuchar in August 2025, it doesn’t promise new money or subsidies. Instead, it asks drugmakers to do one thing: tell the FDA when demand for a critical drug starts to spike. Right now, manufacturers aren’t required to report anything until it’s too late - when shelves are empty and patients are at risk. This bill would force them to notify the agency months in advance, giving regulators time to find alternatives, reroute supplies, or fast-track approvals.

But here’s the catch: no one knows exactly what counts as a "critical drug." The bill doesn’t define it. There’s no timeline for when manufacturers must report. No penalties if they don’t. And no funding to make the FDA’s Drug Shortage Portal work properly. That portal, which should be the central hub for tracking shortages, has been glitching since the shutdown started. FDA staff who monitor it? Furloughed. No one’s updating the list. No one’s calling suppliers.

The other bill, Health Care Provider Shortage Minimization Act of 2025 (H.R.1160), is even murkier. All we know is the title. No sponsors listed in public records. No committee assigned. No text published. It’s supposed to tackle the fact that 122 million Americans live in areas with too few doctors, nurses, or primary care providers. But without details, it’s impossible to say if it’s about loan forgiveness for rural doctors, expanding med school slots, or letting nurse practitioners practice independently. The American Medical Association says 87% of physicians are seeing drug shortages - yet only 12% even knew H.R.1160 existed.

Why These Bills Are Stuck

The government shut down on October 1, 2025. Over 800,000 federal workers were sent home. That includes every single person at the FDA who tracks drug supply chains. It includes the budget analysts at the Congressional Budget Office who’d normally score how much these bills cost. It includes the staff who draft committee reports and schedule hearings.

S.2665 was referred to the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee on day one. That committee hasn’t met since the shutdown. No hearings. No markup. No vote. The same goes for H.R.1160 in the House. Meanwhile, Congress spent weeks arguing over whether senators should be allowed to sue over phone records - a procedural fight with zero impact on patient care.

Even the proposed fix - a continuing resolution to keep the government open through January 30, 2026 - doesn’t mention drugs. Doesn’t mention doctors. Doesn’t mention shortages. It’s just a temporary patch to avoid chaos, with zero new tools to fix the root problems.

Who’s Feeling the Pain?

Hospitals aren’t waiting for Congress. The American Hospital Association surveyed 500 hospitals in Q3 2025. 98% reported at least one critical drug shortage. Some were out of epinephrine. Others couldn’t get insulin for diabetic patients. One hospital in Ohio had to use expired antibiotics because the new batch hadn’t arrived - and the FDA couldn’t verify safety because their inspectors were furloughed.

Manufacturers say 63% of shortages come from production delays - not lack of demand. A single factory in India or China that shuts down for a week can ripple across the entire U.S. supply chain. But right now, there’s no early warning system. No one’s watching. No one’s calling ahead.

And the provider shortage? It’s not getting better. The American Association of Medical Colleges projects a deficit of 124,000 physicians by 2034. Rural clinics are closing. Emergency rooms are turning away patients because there’s no one to staff them. H.R.1160 could help - if anyone knew what it actually said.

What’s Missing From the Debate

There’s a bigger issue no one’s talking about: funding. The Drug Shortage Prevention Act would need about $45 million a year just to staff and upgrade the FDA’s tracking system. That’s less than 0.003% of the federal budget. But right now, Congress is cutting $7.9 billion from foreign aid and $1.1 billion from public media. Those are headline cuts. They get press. They get votes. But no one’s proposing $45 million to keep insulin on the shelf.

And there’s no plan for enforcement. If a company fails to report a surge in demand, what happens? A fine? A public listing? A delay in approval for their next drug? The bill doesn’t say. That’s not oversight - that’s a suggestion.

Even the industry knows this. The Association for Accessible Medicines says generic drug makers are the biggest source of shortages - because they operate on razor-thin margins. A small price drop or a regulatory hiccup can shut down production. But instead of helping them stabilize supply, Congress is letting them stay in the dark.

What Happens Next?

If the shutdown ends before January 30, 2026, and Congress returns to work, S.2665 might get a hearing. Maybe. But it won’t become law unless it’s amended to include clear definitions, penalties, and funding. H.R.1160? It’s already a ghost. Without sponsors stepping forward to release the text, it’s dead on arrival.

If the shutdown continues past January 30, both bills die. Not because they’re bad. But because Congress didn’t act in time. They’ll be reintroduced in January 2027 - after another two-year delay. Meanwhile, patients keep getting sicker. Hospitals keep scrambling. And the same cycle repeats.

The truth is, drug shortages aren’t new. They’ve been getting worse for a decade. What’s new is that Congress finally has bills on the table. But without transparency, funding, and urgency, they’re just paper. And paper doesn’t save lives.

Oladeji Omobolaji

January 22, 2026 AT 18:34This is wild. I live in Nigeria and we deal with drug shortages all the time, but at least here, people just adapt. No one expects the government to fix it. Over here, it’s a national crisis. People are literally dying because a factory in India shut down for a week. And Congress is arguing about phone records? Bro.

Janet King

January 23, 2026 AT 19:43The Drug Shortage Prevention Act lacks enforceable mechanisms. Without statutory penalties, funding, or defined critical drug criteria, the legislation is non-operational. The FDA’s current infrastructure is under-resourced and cannot fulfill its mandated functions during a government shutdown. Legislative inaction constitutes a failure of public health governance.

Anna Pryde-Smith

January 25, 2026 AT 12:06They’re letting people die because some senator’s ego is bigger than a child’s insulin prescription. H.R.1160 doesn’t even have a text?! That’s not incompetence-that’s malice. Someone needs to drag these politicians out of their marble palaces and make them stand in a hospital ER for a week. Just one week. Then we’ll see how fast they move.

Sallie Jane Barnes

January 26, 2026 AT 23:11I work in a rural clinic. We’ve run out of epinephrine twice this year. We’ve had to call patients and say, ‘We can’t give you your chemo on time.’ No one in Congress has ever held a vial of medicine that’s been sitting on a shelf for six months because the FDA can’t inspect it. This isn’t policy. This is cruelty dressed up as procedure.

Kerry Moore

January 28, 2026 AT 14:22It’s concerning that the legislative process has become entirely reactive rather than preventative. The absence of a clear definition for critical drugs, coupled with the lack of funding for the FDA’s tracking system, renders S.2665 functionally inert. The broader systemic issue lies in the prioritization of procedural politics over substantive public health outcomes.

Sue Stone

January 29, 2026 AT 03:00Someone please tell me why we’re still surprised by this. We’ve been here before. Every time a drug runs out, we get mad for a week, then forget. Meanwhile, the same factories in the same countries keep failing, and we keep pretending we didn’t know it was coming.

Dawson Taylor

January 29, 2026 AT 08:49Policy without accountability is theater. Funding without enforcement is charity. Legislation without transparency is noise.

Laura Rice

January 29, 2026 AT 23:53ok so like… i just read this and i’m crying? not even joking. my mom’s on chemo and they had to switch her med 3 times because of shortages. and now congress is playing politics with a bill that doesn’t even have a draft?? like… who’s writing this? why is no one screaming??

Stacy Thomes

January 30, 2026 AT 01:52Enough is enough. We need to call every rep. We need to show up at town halls. We need to make this the issue that wins elections. No more silence. No more waiting. If they won’t act, we’ll make them afraid to sleep.

dana torgersen

January 31, 2026 AT 02:16wait… so the bill… doesn’t even… have a text?? like… is that… legal? or… is this just… how congress… works now?? i mean… i’m not a lawyer… but… this feels… wrong??

charley lopez

February 1, 2026 AT 05:18Supply chain fragility in pharmaceutical manufacturing is exacerbated by globalized production dependencies and insufficient regulatory oversight infrastructure. The absence of real-time demand forecasting protocols and mandatory manufacturer notification thresholds constitutes a systemic vulnerability in the U.S. pharmaceutical distribution network.

Kerry Evans

February 1, 2026 AT 23:45Of course this is happening. You let bureaucrats and generic drug companies run things without consequences, and you get this. The problem isn’t the shutdown-it’s the people who think ‘we’ll fix it later’ is a policy. This isn’t a crisis. It’s a consequence. And it’s going to keep happening until someone gets fired.